1.4 Egrep Metacharacters

Let's start to explore some of the egrep metacharacters that supply its regular expression power. I'll go over them quickly with a few examples, leaving the

detailed examples and descriptions for later chapters.

Typographical Conventions Before we begin, please make sure to review the

typographical conventions explained in the

preface

. This book forges

a bit of new ground in the area of typesetting, so some of my notations may be

unfamiliar at first.

1.4.1 Start and End of the Line

Probably the easiest metacharacters to understand are

^ ^ (caret) and

(caret) and

$ $ (dollar),

which represent the start and end, respectively, of the line of text as it is being

checked. As we've seen, the regular expression

(dollar),

which represent the start and end, respectively, of the line of text as it is being

checked. As we've seen, the regular expression

cat cat finds c·a·t anywhere on the

line, but

finds c·a·t anywhere on the

line, but

^cat ^cat matches only if the c·a·t is at the beginning of the linethe

matches only if the c·a·t is at the beginning of the linethe

^ ^ is

used to effectively anchor the match (of the rest of the regular expression) to the

start of the line. Similarly,

is

used to effectively anchor the match (of the rest of the regular expression) to the

start of the line. Similarly,

cat$ cat$ finds c·a·t only at the end of the line, such as a

line ending with scat.

finds c·a·t only at the end of the line, such as a

line ending with scat.

It's best to get into the habit of interpreting regular expressions in a rather literal

way. For example, don't think

^cat ^cat matches a line with cat at the beginning

matches a line with cat at the beginning

but rather:

^cat ^cat matches if you have the beginning of a line, followed immediately

by c, followed immediately by a, followed immediately by t.

matches if you have the beginning of a line, followed immediately

by c, followed immediately by a, followed immediately by t.

They both end up meaning the same thing, but reading it the more literal way

allows you to intrinsically understand a new expression when you see it. How

would egrep interpret

cat$ cat$ ,

,

^$ ^$ , or even simply

, or even simply

^ ^ alone?

alone?  Click here to

check your interpretations. Click here to

check your interpretations.

The caret and dollar are special in that they match a position in the line rather than

any actual text characters themselves. Of course, there are various ways to actually

match real text. Besides providing literal characters like

cat cat in your regular

expression, you can also use some of the items discussed in the next few sections.

in your regular

expression, you can also use some of the items discussed in the next few sections.

1.4.2 Character Classes

1.4.2.1 Matching any one of several characters

Let's say you want to search for "grey," but also want to find it if it were spelled

"gray." The regular-expression construct

[···] [···] , usually called a character class, lets

you list the characters you want to allow at that point in the match. While

, usually called a character class, lets

you list the characters you want to allow at that point in the match. While

e e matches just an e, and

matches just an e, and

a a matches just an a, the regular expression

matches just an a, the regular expression

[ea] [ea] matches

either. So, then, consider

matches

either. So, then, consider

gr[ea]y gr[ea]y : this means to find " g, followed by r, followed

by either an e or an a, all followed by y ." Because I'm a really poor speller, I'm

always using regular expressions like this against a huge list of English words to

figure out proper spellings. One I use often is

: this means to find " g, followed by r, followed

by either an e or an a, all followed by y ." Because I'm a really poor speller, I'm

always using regular expressions like this against a huge list of English words to

figure out proper spellings. One I use often is

sep[ea]r[ea]te sep[ea]r[ea]te , because I can

never remember whether the word is spelled "seperate," "separate," "separete," or

what. The one that pops up in the list is the proper spelling; regular expressions

to the rescue.

, because I can

never remember whether the word is spelled "seperate," "separate," "separete," or

what. The one that pops up in the list is the proper spelling; regular expressions

to the rescue.

Notice how outside of a class, literal characters (like the

g g and

and

r r of

of

gr[ae]y gr[ae]y )

have an implied "and then" between them "match

)

have an implied "and then" between them "match

g g and then match

and then match

r r . . ." It's

completely opposite inside a character class. The contents of a class is a list of

characters that can match at that point, so the implication is "or."

. . ." It's

completely opposite inside a character class. The contents of a class is a list of

characters that can match at that point, so the implication is "or."

As another example, maybe you want to allow capitalization of a word's first letter,

such as with

[Ss]mith [Ss]mith . Remember that this still matches lines that contain smith

(or Smith) embedded within another word, such as with blacksmith. I don't

want to harp on this throughout the overview, but this issue does seem to be the

source of problems among some new users. I'll touch on some ways to handle this

embedded-word problem after we examine a few more metacharacters.

. Remember that this still matches lines that contain smith

(or Smith) embedded within another word, such as with blacksmith. I don't

want to harp on this throughout the overview, but this issue does seem to be the

source of problems among some new users. I'll touch on some ways to handle this

embedded-word problem after we examine a few more metacharacters.

You can list in the class as many characters as you like. For example,

[123456] [123456] matches any of the listed digits. This particular class might be useful as part of

matches any of the listed digits. This particular class might be useful as part of

<H[123456]> <H[123456]> , which matches <H1>, <H2>, <H3>, etc. This can be useful when searching for HTML headers.

, which matches <H1>, <H2>, <H3>, etc. This can be useful when searching for HTML headers.

Within a character class, the character-class metacharacter '-' (dash) indicates a

range of characters:

<H[1-6]> <H[1-6]> is identical to the previous example.

is identical to the previous example.

[0-9] [0-9] and

and

[a-z] [a-z] are common shorthands for classes to match digits and English lowercase

letters, respectively. Multiple ranges are fine, so

are common shorthands for classes to match digits and English lowercase

letters, respectively. Multiple ranges are fine, so

[0123456789abcdefABCDEF] [0123456789abcdefABCDEF] can

be written as

can

be written as

[0-9a-fA-F] [0-9a-fA-F] (or, perhaps,

(or, perhaps,

[A-Fa-f0-9] [A-Fa-f0-9] , since the order in which

ranges are given doesn't matter). These last three examples can be useful when

processing hexadecimal numbers. You can freely combine ranges with literal characters:

, since the order in which

ranges are given doesn't matter). These last three examples can be useful when

processing hexadecimal numbers. You can freely combine ranges with literal characters:

[0-9A-Z_!.?] [0-9A-Z_!.?] matches a digit, uppercase letter, underscore, exclamation

point, period, or a question mark.

matches a digit, uppercase letter, underscore, exclamation

point, period, or a question mark.

Note that a dash is a metacharacter only within a character class otherwise it

matches the normal dash character. In fact, it is not even always a metacharacter

within a character class. If it is the first character listed in the class, it can't possibly indicate a range, so it is not considered a metacharacter. Along the same lines, the

question mark and period at the end of the class are usually regular-expression

metacharacters, but only when not within a class (so, to be clear, the only special

characters within the class in

[0-9A-Z_!.?] [0-9A-Z_!.?] are the two dashes).

are the two dashes).

Consider character classes as their own mini language. The rules regarding

which metacharacters are supported (and what they do) are completely

different inside and outside of character classes.

We'll see more examples of this shortly.

1.4.2.2 Negated character classes

If you use

[^···] [^···] instead of

instead of

[···] [···] , the class matches any character that isn't listed.

For example,

, the class matches any character that isn't listed.

For example,

[^1-6] [^1-6] matches a character that's not

1 through 6. The leading ^ in

the class "negates" the list, so rather than listing the characters you want to include

in the class, you list the characters you don't want to be included.

matches a character that's not

1 through 6. The leading ^ in

the class "negates" the list, so rather than listing the characters you want to include

in the class, you list the characters you don't want to be included.

You might have noticed that the ^ used here is the same as the start-of-line caret

introduced in Section 1.4.1. The character is the same, but the meaning is completely

different. Just as the English word "wind" can mean different things depending on

the context (sometimes a strong breeze, sometimes what you do to a clock), so

can a metacharacter. We've already seen one example, the range-building dash. It

is valid only inside a character class (and at that, only when not first inside the

class). ^ is a line anchor outside a class, but a class metacharacter inside a class

(but, only when it is immediately after the class's opening bracket; otherwise, it's not special inside a class). Don't fear these are the most complex special cases;

others we'll see later aren't so bad.

As another example, let's search that list of English words for odd words that have q followed by something other than u. Translating that into a regular expression, it becomes

q[^u] q[^u] . I tried it on the list I have, and there certainly weren't many. I did

find a few, including a number of words that I didn't even know were English.

. I tried it on the list I have, and there certainly weren't many. I did

find a few, including a number of words that I didn't even know were English.

Here's what happened. (What I typed is in bold.)

% egrep 'q[^u]' word.list

Iraqi

Iraqian

miqra

qasida

qintar

qoph

zaqqum%

Two notable words not listed are "Qantas", the Australian airline, and "Iraq".

Although both words are in the word.list file, neither were displayed by my egrep

command. Why?  Think about it for a bit, and then click here to check your

reasoning. Think about it for a bit, and then click here to check your

reasoning.

Remember, a negated character class means "match a character that's not listed"

and not "don't match what is listed." These might seem the same, but the Iraq

example shows the subtle difference. A convenient way to view a negated class is

that it is simply a shorthand for a normal class that includes all possible characters

except those that are listed.

1.4.3 Matching Any Character with Dot

The metacharacter

. . (usually called dot or point) is a shorthand for a character

class that matches any character. It can be convenient when you want to have an

"any character here" placeholder in your expression. For example, if you want to

search for a date such as 03/19/76, 03-19-76, or even 03.19.76, you could go

to the trouble to construct a regular expression that uses character classes to

explicitly allow '/', '-', or '.' between each number, such as

(usually called dot or point) is a shorthand for a character

class that matches any character. It can be convenient when you want to have an

"any character here" placeholder in your expression. For example, if you want to

search for a date such as 03/19/76, 03-19-76, or even 03.19.76, you could go

to the trouble to construct a regular expression that uses character classes to

explicitly allow '/', '-', or '.' between each number, such as

03[-./]19[-./]76 03[-./]19[-./]76 .

However, you might also try simply using

.

However, you might also try simply using

03.19.76 03.19.76 .

.

Quite a few things are going on with this example that might be unclear at first. In

03[-./]19[-./]76 03[-./]19[-./]76 , the dots are not metacharacters because they are within a

character class. (Remember, the list of metacharacters and their meanings are different inside and outside of character classes.) The dashes are also not class metacharacters

in this case because each is the first thing after [ or [^. Had they not

been first, as with

, the dots are not metacharacters because they are within a

character class. (Remember, the list of metacharacters and their meanings are different inside and outside of character classes.) The dashes are also not class metacharacters

in this case because each is the first thing after [ or [^. Had they not

been first, as with

[.-/] [.-/] , it they would be the class range metacharacter, which

would be a mistake in this situation.

, it they would be the class range metacharacter, which

would be a mistake in this situation.

With

03.19.76 03.19.76 , the dots are metacharacters ones that match any character

(including the dash, period, and slash that we are expecting). However, it is

important to know that each dot can match any character at all, so it can match,

say, 'lottery numbers: 19 203319 7639'.

, the dots are metacharacters ones that match any character

(including the dash, period, and slash that we are expecting). However, it is

important to know that each dot can match any character at all, so it can match,

say, 'lottery numbers: 19 203319 7639'.

So,

03[-./]19[-./]76 03[-./]19[-./]76 is more precise, but it's more difficult to read and write.

is more precise, but it's more difficult to read and write.

03.19.76 03.19.76 is easy to understand, but vague. Which should we use? It all depends

upon what you know about the data being searched, and just how specific you

feel you need to be. One important, recurring issue has to do with balancing your

knowledge of the text being searched against the need to always be exact when

writing an expression. For example, if you know that with your data it would be highly unlikely for

is easy to understand, but vague. Which should we use? It all depends

upon what you know about the data being searched, and just how specific you

feel you need to be. One important, recurring issue has to do with balancing your

knowledge of the text being searched against the need to always be exact when

writing an expression. For example, if you know that with your data it would be highly unlikely for

03.19.76 03.19.76 to match in an unwanted place, it would certainly

be reasonable to use it. Knowing the target text well is an important part of wielding

regular expressions effectively.

to match in an unwanted place, it would certainly

be reasonable to use it. Knowing the target text well is an important part of wielding

regular expressions effectively.

1.4.4 Alternation

1.4.4.1 Matching any one of several subexpressions

A very convenient metacharacter is

| | , which means "or." It allows you to combine

multiple expressions into a single expression that matches any of the individual

ones. For example,

, which means "or." It allows you to combine

multiple expressions into a single expression that matches any of the individual

ones. For example,

Bob Bob and

and

Robert Robert are separate expressions, but

are separate expressions, but

Bob|Robert Bob|Robert is

one expression that matches either. When combined this way, the subexpressions

are called alternatives.

is

one expression that matches either. When combined this way, the subexpressions

are called alternatives.

Looking back to our

gr[ea]y gr[ea]y example, it is interesting to realize that it can be

written as

example, it is interesting to realize that it can be

written as

grey|gray grey|gray , and even

, and even

gr(a|e)y gr(a|e)y . The latter case uses parentheses to

constrain the alternation. (For the record, parentheses are metacharacters too.)

Note that something like

. The latter case uses parentheses to

constrain the alternation. (For the record, parentheses are metacharacters too.)

Note that something like

gr[a|e]y gr[a|e]y is not what we want within a class, the '|'

character is just a normal character, like

is not what we want within a class, the '|'

character is just a normal character, like

a a and

and

e e .

.

With

gr(a|e)y gr(a|e)y , the parentheses are required because without them,

, the parentheses are required because without them,

gra|ey gra|ey means "

means "

gra gra or

or

ey ey ," which is not what we want here. Alternation reaches far, but

not beyond parentheses. Another example is

," which is not what we want here. Alternation reaches far, but

not beyond parentheses. Another example is

(First|1st)•[Ss]treet (First|1st)•[Ss]treet .

Actually, since both

.

Actually, since both

First First and

and

1st 1st end with

end with

st st , the combination can be shortened to

, the combination can be shortened to

(Fir|1)st•[Ss]treet (Fir|1)st•[Ss]treet . That's not necessarily quite as easy to read, but be sure to

understand that

. That's not necessarily quite as easy to read, but be sure to

understand that

(first|1st) (first|1st) and

and

(fir|1)st (fir|1)st effectively mean the same thing.

effectively mean the same thing.

Here's an example involving an alternate spelling of my name. Compare and contrast

the following three expressions, which are all effectively the same:

Jeffrey|Jeffery

Jeff(rey|ery)

Jeff(re|er)y

To have them match the British spellings as well, they could be:

(Geoff|Jeff)(rey|ery)

(Geo|Je)ff(rey|ery)

(Geo|Je)ff(re|er)y

Finally, note that these three match effectively the same as the longer (but simpler)

Jeffrey|Geoffery|Jeffery|Geoffrey Jeffrey|Geoffery|Jeffery|Geoffrey . They're all different ways to specify the

same desired matches.

. They're all different ways to specify the

same desired matches.

Although the

gr[ea]y gr[ea]y versus

versus

gr(a|e)y gr(a|e)y examples might blur the distinction, be

careful not to confuse the concept of alternation with that of a character class. A

character class can match just a single character in the target text. With alternation,

since each alternative can be a full-fledged regular expression in and of itself, each alternative can match an arbitrary amount of text. Character classes are almost like

their own special mini-language (with their own ideas about metacharacters, for

example), while alternation is part of the "main" regular expression language.

You'll find both to be extremely useful.

examples might blur the distinction, be

careful not to confuse the concept of alternation with that of a character class. A

character class can match just a single character in the target text. With alternation,

since each alternative can be a full-fledged regular expression in and of itself, each alternative can match an arbitrary amount of text. Character classes are almost like

their own special mini-language (with their own ideas about metacharacters, for

example), while alternation is part of the "main" regular expression language.

You'll find both to be extremely useful.

Also, take care when using caret or dollar in an expression that has alternation.

Compare

^From|Subject|Date:• ^From|Subject|Date:• with

with

^(From|Subject|Date):• ^(From|Subject|Date):• . Both appear

similar to our earlier email example, but what each matches (and therefore how

useful it is) differs greatly. The first is composed of three alternatives, so it matches

"

. Both appear

similar to our earlier email example, but what each matches (and therefore how

useful it is) differs greatly. The first is composed of three alternatives, so it matches

"

^From ^From or

or

Subject Subject or

or

Date:• Date:• ," which is not particularly useful. We want the

leading caret and trailing

," which is not particularly useful. We want the

leading caret and trailing

:• :• to apply to each alternative. We can accomplish this

by using parentheses to "constrain" the alternation:

to apply to each alternative. We can accomplish this

by using parentheses to "constrain" the alternation:

^(From|Subject|Date):•

The alternation is constrained by the parentheses, so literally, this regex means

"match the start of the line, then one of

From From ,

,

Subject Subject , or

, or

Date Date , and then match

, and then match

:• :• ." Effectively, it matches:

." Effectively, it matches:

1) start-of-line, followed by F·r·o·m, followed by ':•'

or 2) start-of-line, followed by S·u·b·j·e·c·t, followed by ':•'

or 3) start-of-line, followed by D·a·t·e, followed by ':•'

Putting it less literally, it matches lines beginning with 'From:•', 'Subject:•', or

'Date:•', which is quite useful for listing the messages in an email file.

Here's an example:

% egrep '^(From|Subject|Date): ' mailbox

From: elvis@tabloid.org (The King)

Subject: be seein' ya around

Date: Thu, 22 Aug 2002 11:04:13

From: The Prez <president@whitehouse.gov>

Date: Tue, 27 Aug 2002 8:36:24

Subject: now, about your vote···

.

.

.

1.4.5 Ignoring Differences in Capitalization

This email header example provides a good opportunity to introduce the concept

of a case-insensitive match. The field types in an email header usually appear with

leading capitalization, such as "Subject" and "From," but the email standard actually

allows mixed capitalization, so things like "DATE" and "from" are also allowed.

Unfortunately, the regular expression in the previous section doesn't match those.

One approach is to replace

From From with

with

[Ff][Rr][Oo][Mm] [Ff][Rr][Oo][Mm] to match any form of

"from," but this is quite cumbersome, to say the least. Fortunately, there is a way to

tell egrep to ignore case when doing comparisons, i.e., to perform the match in a

case insensitive manner in which capitalization differences are simply ignored. It is not a part of the regular-expression language, but is a related useful feature many

tools provide. egrep's command-line option "-i" tells it to do a case-insensitive

match. Place -i on the command line before the regular expression:

to match any form of

"from," but this is quite cumbersome, to say the least. Fortunately, there is a way to

tell egrep to ignore case when doing comparisons, i.e., to perform the match in a

case insensitive manner in which capitalization differences are simply ignored. It is not a part of the regular-expression language, but is a related useful feature many

tools provide. egrep's command-line option "-i" tells it to do a case-insensitive

match. Place -i on the command line before the regular expression:

% egrep -i '^(From|Subject|Date): ' mailbox

This brings up all the lines we matched before, but also includes lines such as:

SUBJECT: MAKE MONEY FAST

I find myself using the -i option quite frequently (perhaps related to the footnote

in Section 1.7.2!) so I recommend keeping it in mind. We'll see other convenient support

features like this in later chapters.

1.4.6 Word Boundaries

A common problem is that a regular expression that matches the word you want

can often also match where the "word" is embedded within a larger word. I mentioned

this briefly in the cat, gray, and Smith examples. It turns out, though, that

some versions of egrep offer limited support for word recognition: namely the ability

to match the boundary of a word (where a word begins or ends).

You can use the (perhaps odd looking) metasequences

\< \< and

and

\> \> if your version

happens to support them (not all versions of egrep do). You can think of them as

word-based versions of

if your version

happens to support them (not all versions of egrep do). You can think of them as

word-based versions of

^ ^ and

and

$ $ that match the position at the start and end of a

word, respectively. Like the line anchors caret and dollar, they anchor other parts

of the regular expression but don't actually consume any characters during a

match. The expression

that match the position at the start and end of a

word, respectively. Like the line anchors caret and dollar, they anchor other parts

of the regular expression but don't actually consume any characters during a

match. The expression

\<cat\> \<cat\> literally means " match if we can find a start-of-word

position, followed immediately by c·a·t, followed immediately by an end-of-word position ." More naturally, it means "find the word cat." If you wanted,

you could use

literally means " match if we can find a start-of-word

position, followed immediately by c·a·t, followed immediately by an end-of-word position ." More naturally, it means "find the word cat." If you wanted,

you could use

\<cat \<cat or

or

cat\> cat\> to find words starting and ending with cat.

to find words starting and ending with cat.

Note that

< < and

and

> > alone are not metacharacters when combined with a backslash,

the sequences become special. This is why I called them "metasequences."

It's their special interpretation that's important, not the number of characters, so

for the most part I use these two meta-words interchangeably.

alone are not metacharacters when combined with a backslash,

the sequences become special. This is why I called them "metasequences."

It's their special interpretation that's important, not the number of characters, so

for the most part I use these two meta-words interchangeably.

Remember, not all versions of egrep support these word-boundary metacharacters,

and those that do don't magically understand the English language. The "start of a

word" is simply the position where a sequence of alphanumeric characters begins;

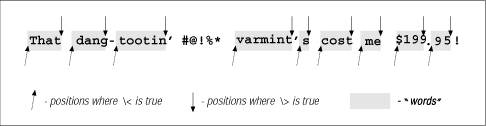

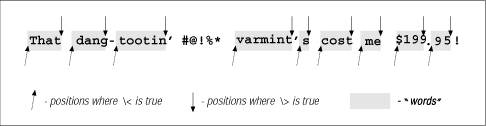

"end of word" is where such a sequence ends. Figure 1-2 shows

a sample line with these positions marked.

The word-starts (as egrep recognizes them) are marked with up arrows, the wordends

with down arrows. As you can see, "start and end of word" is better phrased

as "start and end of an alphanumeric sequence," but perhaps that's too much of a

mouthful.

1.4.7 In a Nutshell

Table 1-1 summarizes the metacharacters we have seen so far.

Table 1. Summary of Metacharacters Seen So Far|

|

.

[···]

[^···]

|

dot

character class

negated character class

|

any one character

any character listed

any character not listed

| |

^

$

\<

\>

|

caret

dollar

backslash less-than

backslash greater-than

|

the position at the start of the line

the position at the end of the line

the position at the start of a word

the position at the end of a word

| |

|

(···)

|

or; bar

parentheses

|

matches either expression it separates

used to limit scope of

| | , plus additional uses yet to be discussed

, plus additional uses yet to be discussed

|

In addition to the table, important points to remember include:

The rules about which characters are and aren't metacharacters (and exactly

what they mean) are different inside a character class. For example, dot is a

metacharacter outside of a class, but not within one. Conversely, a dash is a

metacharacter within a class (usually), but not outside. Moreover, a caret has

one meaning outside, another if specified inside a class immediately after the

opening [, and a third if given elsewhere in the class. Don't confuse alternation with a character class. The class

[abc] [abc] and the alternation

and the alternation

(a|b|c) (a|b|c) effectively mean the same thing, but the similarity in this

example does not extend to the general case. A character class can match

exactly one character, and that's true no matter how long or short the speci-

fied list of acceptable characters might be.

effectively mean the same thing, but the similarity in this

example does not extend to the general case. A character class can match

exactly one character, and that's true no matter how long or short the speci-

fied list of acceptable characters might be. Alternation, on the other hand, can have arbitrarily long alternatives, each textually

unrelated to the other:

\<(1,000,000|million|thousand•thou)\> \<(1,000,000|million|thousand•thou)\> .

However, alternation can't be negated like a character class.

.

However, alternation can't be negated like a character class. A negated character class is simply a notational convenience for a normal

character class that matches everything not listed. Thus,

[^x] [^x] doesn't mean

" match unless there is an x ," but rather " match if there is something that is

not x ." The difference is subtle, but important. The first concept matches a

blank line, for example, while

doesn't mean

" match unless there is an x ," but rather " match if there is something that is

not x ." The difference is subtle, but important. The first concept matches a

blank line, for example, while

[^x] [^x] does not.

does not. The useful -i option discounts capitalization during a match (see Section 1.4.6).

What we have seen so far can be quite useful, but the real power comes from

optional and counting elements, which we'll look at next.

1.4.8 Optional Items

Let's look at matching color or colour. Since they are the same except that one

has a u and the other doesn't, we can use

colou?r colou?r to match either. The metacharacter

to match either. The metacharacter

? ? (question mark) means optional. It is placed after the character that is

allowed to appear at that point in the expression, but whose existence isn't actually

required to still be considered a successful match.

(question mark) means optional. It is placed after the character that is

allowed to appear at that point in the expression, but whose existence isn't actually

required to still be considered a successful match.

Unlike other metacharacters we have seen so far, the question mark attaches only

to the immediately-preceding item. Thus,

colou?r colou?r is interpreted as "

is interpreted as "

c c then

then

o o then

then

l l then

then

o o then

then

u? u? then

then

r r . "

. "

The

u? u? part is always successful: sometimes it matches a u in the text, while other

times it doesn't. The whole point of the ?-optional part is that it's successful either

way. This isn't to say that any regular expression that contains ? is always successful.

For example, against 'semicolon', both

part is always successful: sometimes it matches a u in the text, while other

times it doesn't. The whole point of the ?-optional part is that it's successful either

way. This isn't to say that any regular expression that contains ? is always successful.

For example, against 'semicolon', both

colo colo and

and

u? u? are successful (matching

colo and nothing, respectively). However, the final

are successful (matching

colo and nothing, respectively). However, the final

r r fails, and that's what disallows

semicolon, in the end, from being matched by

fails, and that's what disallows

semicolon, in the end, from being matched by

colou?r colou?r .

.

As another example, consider matching a date that represents July fourth, with the

"July" part being either July or Jul, and the "fourth" part being fourth, 4th, or

simply 4. Of course, we could just use

(July|Jul)•(fourth|4th|4) (July|Jul)•(fourth|4th|4) , but let's

explore other ways to express the same thing.

, but let's

explore other ways to express the same thing.

First, we can shorten the

(July|Jul) (July|Jul) to

to

(July?) (July?) . Do you see how they are effectively

the same? The removal of the

. Do you see how they are effectively

the same? The removal of the  | | means that the parentheses are no longer

really needed. Leaving the parentheses doesn't hurt, but with them removed, means that the parentheses are no longer

really needed. Leaving the parentheses doesn't hurt, but with them removed,

July? July? is a bit less cluttered. This leaves us with

is a bit less cluttered. This leaves us with

July?•(fourth|4th|4) July?•(fourth|4th|4) .

.

Moving now to the second half, we can simplify the

4th|4 4th|4 to

to

4(th)? 4(th)? . As you

can see,

. As you

can see,

? ? can attach to a parenthesized expression. Inside the parentheses can be

as complex a subexpression as you like, but "from the outside" it is considered a

single unit. Grouping for

can attach to a parenthesized expression. Inside the parentheses can be

as complex a subexpression as you like, but "from the outside" it is considered a

single unit. Grouping for

? ? (and other similar metacharacters which I'll introduce

momentarily) is one of the main uses of parentheses.

(and other similar metacharacters which I'll introduce

momentarily) is one of the main uses of parentheses.

Our expression now looks like

July?•(fourth|4(th)?) July?•(fourth|4(th)?)

. Although there are a

fair number of metacharacters, and even nested parentheses, it is not that difficult

to decipher and understand. This discussion of two essentially simple examples

has been rather long, but in the meantime we have covered tangential topics that

add a lot, if perhaps only subconsciously, to our understanding of regular expressions.

Also, it's given us some experience in taking different approaches toward

the same goal. As we advance through this book (and through to a better understanding),

you'll find many opportunities for creative juices to flow while trying to

find the optimal way to solve a complex problem. Far from being some stuffy science,

writing regular expressions is closer to an art.

. Although there are a

fair number of metacharacters, and even nested parentheses, it is not that difficult

to decipher and understand. This discussion of two essentially simple examples

has been rather long, but in the meantime we have covered tangential topics that

add a lot, if perhaps only subconsciously, to our understanding of regular expressions.

Also, it's given us some experience in taking different approaches toward

the same goal. As we advance through this book (and through to a better understanding),

you'll find many opportunities for creative juices to flow while trying to

find the optimal way to solve a complex problem. Far from being some stuffy science,

writing regular expressions is closer to an art.

1.4.9 Other Quantifiers: Repetition

Similar to the question mark are

+ + (plus) and

(plus) and

* * (an asterisk, but as a regularexpr

ession metacharacter, I prefer the term star). The metacharacter

(an asterisk, but as a regularexpr

ession metacharacter, I prefer the term star). The metacharacter

+ + means "one

or more of the immediately-preceding item," and

means "one

or more of the immediately-preceding item," and

* * means "any number, including

none, of the item." Phrased differently,

means "any number, including

none, of the item." Phrased differently,

···* ···* means "try to match it as many times

as possible, but it's okay to settle for nothing if need be." The construct with plus,

means "try to match it as many times

as possible, but it's okay to settle for nothing if need be." The construct with plus,

···+ ···+ , is similar in that it also tries to match as many times as possible, but different

in that it fails if it can't match at least once. These three metacharacters, question

mark, plus, and star, are called quantifiers because they influence the quantity of

what they govern.

, is similar in that it also tries to match as many times as possible, but different

in that it fails if it can't match at least once. These three metacharacters, question

mark, plus, and star, are called quantifiers because they influence the quantity of

what they govern.

Like

···? ···? , the

, the

···* ···* part of a regular expression always succeeds, with the only issue

being what text (if any) is matched. Contrast this to

part of a regular expression always succeeds, with the only issue

being what text (if any) is matched. Contrast this to

···+ ···+ , which fails unless the

item matches at least once.

, which fails unless the

item matches at least once.

For example,

•? •? allows a single optional space, but

allows a single optional space, but

•* •* allows any number of optional spaces. We can use this to make Section 1.4.2's <H[1-6]> example flexible. The HTML specification

says that spaces are allowed immediately before the closing >, such as with <H3•> and <H4•••>. Inserting

allows any number of optional spaces. We can use this to make Section 1.4.2's <H[1-6]> example flexible. The HTML specification

says that spaces are allowed immediately before the closing >, such as with <H3•> and <H4•••>. Inserting

•* •* into our regular expression where we want to allow (but not require) spaces, we get <H[1-6]•*>. This still matches

<H1>, as no spaces are required, but it also flexibly picks up the other versions.

into our regular expression where we want to allow (but not require) spaces, we get <H[1-6]•*>. This still matches

<H1>, as no spaces are required, but it also flexibly picks up the other versions.

Exploring further, let's search for an HTML tag such as <HR•SIZE=14>, which indicates

that a line (a Horizontal Rule) 14 pixels thick should be drawn across the

screen. Like the <H3> example, optional spaces are allowed before the closing

angle bracket. Additionally, they are allowed on either side of the equal sign.

Finally, one space is required between the HR and SIZE, although more are

allowed. To allow more, we could just add

•* •* to the

to the

• • already there, but instead

let's change it to

already there, but instead

let's change it to

•+ •+ . The plus allows extra spaces while still requiring at least one,

so it's effectively the same as

. The plus allows extra spaces while still requiring at least one,

so it's effectively the same as

••* ••* , but more concise. All these changes leave us

with

, but more concise. All these changes leave us

with

<HR•+SIZE•*=•*14•*> <HR•+SIZE•*=•*14•*> .

.

Although flexible with respect to spaces, our expression is still inflexible with

respect to the size given in the tag. Rather than find tags with only one particular

size such as 14, we want to find them all. To accomplish this, we replace the

14 14 with an expression to find a general number. Well, in this case, a "number" is one

or more digits. A digit is

with an expression to find a general number. Well, in this case, a "number" is one

or more digits. A digit is

[0-9] [0-9] , and "one or more" adds a plus, so we end up

replacing

, and "one or more" adds a plus, so we end up

replacing

14 14 by

by

[0-9]+ [0-9]+ . (A character class is one "unit," so can be subject directly

to plus, question mark, and so on, without the need for parentheses.)

. (A character class is one "unit," so can be subject directly

to plus, question mark, and so on, without the need for parentheses.)

This leaves us with

<HR•+SIZE•*=•*[0-9]+•*> <HR•+SIZE•*=•*[0-9]+•*> , which is certainly a

mouthful even though I've presented it with the metacharacters bold, added a bit

of spacing to make the groupings more apparent, and am using the "visible space" symbol '•'

for clarity. (Luckily, egrep has the -i case-insensitive option, see Section 1.4.6, which means

I don't have to use

, which is certainly a

mouthful even though I've presented it with the metacharacters bold, added a bit

of spacing to make the groupings more apparent, and am using the "visible space" symbol '•'

for clarity. (Luckily, egrep has the -i case-insensitive option, see Section 1.4.6, which means

I don't have to use

[Hh][Rr] [Hh][Rr] instead of

instead of

HR HR .) The unadorned regular expression

.) The unadorned regular expression

<HR +SIZE *= *[0-9]+ *> <HR +SIZE *= *[0-9]+ *> likely appears even more confusing. This example looks particularly odd because the subjects of most of the stars and pluses are

space characters, and our eye has always been trained to treat spaces specially. That's a habit you will have to break when reading regular expressions, because

the space character is a normal character, no different from, say, j or 4. (In

later chapters, we'll see that some other tools support a special mode in which

whitespace is ignored, but egrep has no such mode.)

likely appears even more confusing. This example looks particularly odd because the subjects of most of the stars and pluses are

space characters, and our eye has always been trained to treat spaces specially. That's a habit you will have to break when reading regular expressions, because

the space character is a normal character, no different from, say, j or 4. (In

later chapters, we'll see that some other tools support a special mode in which

whitespace is ignored, but egrep has no such mode.)

Continuing to exploit a good example, let's consider that the size attribute is

optional, so you can simply use <HR> if the default size is wanted. (Extra spaces

are allowed before the >, as always.) How can we modify our regular expression

so that it matches either type? The key is realizing that the size part is optional

(that's a hint).  Click here to check your answer. Click here to check your answer.

Take a good look at our latest expression (in the answer box) to appreciate the

differences among the question mark, star, and plus, and what they really mean in

practice. Table 1-2 summarizes their meanings.

Note that each quantifier has some minimum number of matches required to succeed,

and a maximum number of matches that it will ever attempt. With some, the

minimum number is zero; with some, the maximum number is unlimited.

Table 2. Summary of Quantifier "Repetition Metacharacters"|

|

?

*

+

|

none

none

1

|

1

no limit

no limit

|

one allowed; none required ("one optional")

unlimited allowed; none required ("any amount okay")

unlimited allowed; one required ("at least one")

|

1.4.9.1 Defined range of matches: intervals

Some versions of egrep support a metasequence for providing your own minimum

and maximum:

···{

min,max

} ···{

min,max

} . This is called the interval quantifier. For example,

. This is called the interval quantifier. For example,

···{3,12} ···{3,12} matches up to 12 times if possible, but settles for three. One might use

matches up to 12 times if possible, but settles for three. One might use

[a-zA-Z]{1,5} [a-zA-Z]{1,5} to match a US stock ticker (from one to five letters). Using this

notation, {0,1} is the same as a question mark.

to match a US stock ticker (from one to five letters). Using this

notation, {0,1} is the same as a question mark.

Not many versions of egrep support this notation yet, but many other tools do, so

it's covered in Chapter 3 when we look in detail at the broad spectrum of metacharacters

in common use today.

1.4.10 Parentheses and Backreferences

So far, we have seen two uses for parentheses: to limit the scope of alternation,

| | ,

and to group multiple characters into larger units to which you can apply quanti-

fiers like question mark and star. I'd like to discuss another specialized use that's

not common in egrep (although GNU's popular version does support it), but which

is commonly found in many other tools.

,

and to group multiple characters into larger units to which you can apply quanti-

fiers like question mark and star. I'd like to discuss another specialized use that's

not common in egrep (although GNU's popular version does support it), but which

is commonly found in many other tools.

In many regular-expression flavors, parentheses can "remember" text matched by

the subexpression they enclose. We'll use this in a partial solution to the doubledword

problem at the beginning of this chapter. If you knew the the specific doubled

word to find (such as "the" earlier in this sentence did you catch it?), you

could search for it explicitly, such as with

the•the

the•the

. In this case, you would also

find items such as

the•theory, but you could easily get around that problem if

your egrep supports the word-boundary metasequences

. In this case, you would also

find items such as

the•theory, but you could easily get around that problem if

your egrep supports the word-boundary metasequences

\<···\> \<···\> mentioned in

Section 1.4.6:

mentioned in

Section 1.4.6:

\<the•the\> \<the•the\> . We could use

. We could use

•+ •+ for the space for even more flexibility.

for the space for even more flexibility.

However, having to check for every possible pair of words would be an impossible

task. Wouldn't it be nice if we could match one generic word, and then say

"now match the same thing again"? If your egrep supports backreferencing, you

can. Backreferencing is a regular-expression feature that allows you to match new

text that is the same as some text matched earlier in the expression.

We start with

\<the•+the\> \<the•+the\> and replace the initial

and replace the initial

the the with a regular expression

to match a general word, say

with a regular expression

to match a general word, say

[A-Za-z]+ [A-Za-z]+ . Then, for reasons that will become clear

in the next paragraph, let's put parentheses around it. Finally, we replace the second

'the' by the special metasequence

. Then, for reasons that will become clear

in the next paragraph, let's put parentheses around it. Finally, we replace the second

'the' by the special metasequence

\1 \1 . This yields

. This yields

\<([A-Za-z]+)•+\1\> \<([A-Za-z]+)•+\1\> .

.

With tools that support backreferencing, parentheses "remember" the text that the

subexpression inside them matches, and the special metasequence

\1 \1 represents

that text later in the regular expression, whatever it happens to be at the time.

represents

that text later in the regular expression, whatever it happens to be at the time.

Of course, you can have more than one set of parentheses in a regular expression.

Use

\1 \1 ,

,

\2 \2 ,

,

\3 \3 , etc., to refer to the first, second, third, etc. sets. Pairs of parentheses

are numbered by counting opening parentheses from the left, so with

, etc., to refer to the first, second, third, etc. sets. Pairs of parentheses

are numbered by counting opening parentheses from the left, so with

([a-z])([0-9])\1\2 ([a-z])([0-9])\1\2 , the

, the

\1 \1 refers to the text matched by

refers to the text matched by

[a-z] [a-z] , and

, and

\2 \2 refers

to the text matched by

refers

to the text matched by

[0-9] [0-9] .

.

With our 'the•the' example,

[A-Za-z]+ [A-Za-z]+ matches the first 'the'. It is within the

first set of parentheses, so the 'the' matched becomes available via

matches the first 'the'. It is within the

first set of parentheses, so the 'the' matched becomes available via

\1 \1 . If the following

. If the following

•+ •+ matches, the subsequent

matches, the subsequent

\1 \1 will require another 'the'. If

will require another 'the'. If

\1 \1 is successful,

then

is successful,

then

\> \> makes sure that we are now at an end-of-word boundary (which we

wouldn't be were the text 'the•theft'). If successful, we've found a repeated

word. It's not always the case that that is an error (such as with "that" in this sentence),

but that's for you to decide once the suspect lines are shown.

makes sure that we are now at an end-of-word boundary (which we

wouldn't be were the text 'the•theft'). If successful, we've found a repeated

word. It's not always the case that that is an error (such as with "that" in this sentence),

but that's for you to decide once the suspect lines are shown.

When I decided to include this example, I actually tried it on what I had written so

far. (I used a version of egrep that supports both

\<···\> \<···\> and backreferencing.) To

make it more useful, so that 'The•the' would also be found, I used the case-insensitive

-i option mentioned in Section 1.4.6.

and backreferencing.) To

make it more useful, so that 'The•the' would also be found, I used the case-insensitive

-i option mentioned in Section 1.4.6.

Here's the command I ran:

% egrep -i '\<([a-z]+) +\1\>' files···

I was surprised to find fourteen sets of mistakenly 'doubled•doubled' words! I

corrected them, and since then have built this type of regular-expression check

into the tools that I use to produce the final output of this book, to ensure none

creep back in.

As useful as this regular expression is, it is important to understand its limitations.

Since egrep considers each line in isolation, it isn't able to find when the ending

word of one line is repeated at the beginning of the next. For this, a more flexible

tool is needed, and we will see some examples in the next chapter.

1.4.11 The Great Escape

One important thing I haven't mentioned yet is how to actually match a character

that a regular expression would normally interpret as a metacharacter. For example,

if I searched for the Internet hostname ega.att.com using

ega.att.com ega.att.com , it

could end up matching something like megawatt•computing. Remember,

, it

could end up matching something like megawatt•computing. Remember,

. . is a

metacharacter that matches any character, including a space.

is a

metacharacter that matches any character, including a space.

The metasequence to match an actual period is a period preceded by a backslash:

ega\.att\.com ega\.att\.com . The sequence

. The sequence

\. \. is described as an escaped period or escaped dot, and you can do this with all the normal metacharacters, except in a characterclass.

is described as an escaped period or escaped dot, and you can do this with all the normal metacharacters, except in a characterclass.

A backslash used in this way is called an "escape" when a metacharacter is

escaped, it loses its special meaning and becomes a literal character. If you like,

you can consider the sequence to be a special metasequence to match the literal

character. It's all the same.

As another example, you could use

\([a-zA-Z]+\)

\([a-zA-Z]+\)

to match a word within

parentheses, such as '(very)'. The backslashes in the

to match a word within

parentheses, such as '(very)'. The backslashes in the

\( \( and

and

\) \) sequences

remove the special interpretation of the parentheses, leaving them as literals to

match parentheses in the text.

sequences

remove the special interpretation of the parentheses, leaving them as literals to

match parentheses in the text.

When used before a non-metacharacter, a backslash can have different meanings

depending upon the version of the program. For example, we have already seen

how some versions treat

\< \< ,

,

\> \> ,

,

\1 \1 , etc. as metasequences. We will see many

more examples in later chapters.

, etc. as metasequences. We will see many

more examples in later chapters.

|